The numbers, each like an individual grain of salt, keep mounting as the World Health Organization (WHO) tells us that there are as many as 2.5 million excess deaths each year globally because of our salt intake; each of which, the public health body believes, could be avoided if sodium consumption was cut by 30%.

Such an endeavour is no mean feat. In the US, for example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says the average person consumes 3,400mg each day, 50% more than the recommended 2,300mg. Upon reading that, most people would be inclined to take the salt from the dinner table. But according to Dr Tom Frieden, president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, it’s not that simple. “That’s actually a very, very small portion of the total use in almost all countries. That’s a real misconception,” he explains. The former director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene says the real problem comes from the sodium in our food ingredients and what is added during cooking. In places like India and China, for example, salt is used “literally by the handful”, he says. It’s a view supported by the numbers; low-to-middle income countries account for four in every five of those 2.5 million deaths annually, according to Resolve to Save Lives.

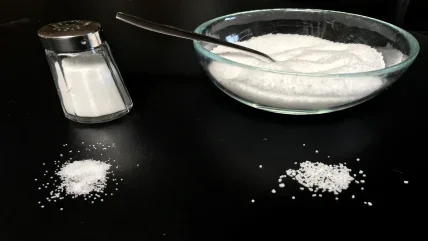

Take it with a pinch of salt

Funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Gates Philanthropy Partners, among others, Resolve to Save Lives was established in 2017. Its main objective is to form partnerships with national and local organisations in low and middle-income countries to co-create, advocate for and scale up activities in heart disease prevention and epidemic preparedness. Its aim is to save 100 million lives over a 30-year period by helping countries improve their preparedness for epidemics and pandemics, eliminating trans fats, improving the treatment of hypertension in primary care and reducing salt intake.

Its work is closely tied to efforts by the WHO to achieve the 30% reduction in sodium consumption by 2025. However, those efforts are off track according to the United Nations agency that in March 2023 warned just 5% of its member states were protected by mandatory and comprehensive sodium reduction policies. It said a staggering 73% lacked policies that would help achieve the reduction targets; just nine countries – Brazil, Chile, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Malaysia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Spain and Uruguay – have a “comprehensive package of recommended policies” it says.

A grainy situation

Speaking at the release of a damning report on the issue, WHO Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “Unhealthy diets are a leading cause of death and disease globally, and excessive sodium intake is one of the main culprits. This report shows that most countries are yet to adopt any mandatory sodium reduction policies, leaving their people at risk of heart attack, stroke, and other health problems.” He called on all countries to act and for manufacturers to implement the WHO benchmarks for sodium content in food.

Frieden warns that although progress had been made, it was slowing or even stalling. “I think sodium reduction has been one of the hardest areas,” he says. The UK is a good example of that; he says there have been some good progress made for five to ten years, but then the government backed off and that progress stopped. That, he adds, is a real lesson: “If the government sets a level playing field, industry can be unharmed, even helped. But if the government calls for voluntary measures, they almost invariably fail.”

It’s a view echoed in research released just days after speaking with Frieden. The study by Queen Mary University of London and published in the Journal of Hypertension concluded that thousands of lives in England were being put at risk by a failure of governments to reduce salt intake since 2014. At the same time, Action on Salt along with 33 leading experts and health charities, called for a mandatory and comprehensive programme to tackle the issue.

It seems that such measures would have public support. Action on Salt – established in the mid- 1990s to find consensus between government and the food industry to reduce salt intake – said it found nine out of ten polled would support government action to protect the public from avoidable health conditions such as heart disease and strokes, with almost 80% said ministers should do more to help cut salt consumption.

12%

The targeted sodium reduction in food products in the US by 2024.

US Food & Drug Administration

A stubborn industry

The largest hurdle facing sodium reduction targets is that they are pitted against a food industry arguably unwilling to change. “I think most companies would rather not change. There’s a certain financial and human cost of change. So, inertia is a very powerful force,” explains Frieden. But, he adds, the simple fact is salt can be reduced by as much as 15% in food products largely without consumers noticing. The next step would be to replace traditional sodium salt with potassium-enriched substitute to reach that holy grail of a 30% sodium reduction.

11.8%

The percentage of annual growth in the global sodium replacement market between 2020–25.

Mordor Intelligence

Frieden acknowledges there are challenges in doing so, including the higher cost of potassium and the risk of consumer disquiet were they to notice a change in taste. But, he says, those two measures alone would help reach the target and positively impact human health. “You get a double or triple benefit by reducing sodium, increasing potassium and improving the sodium-to-potassium ratio,” he says.

There are some concerns about the risks of potassium consumption for people with kidney problems, though, but as Frieden says, there needs to be some perspective. “If you have kidney failure, you shouldn’t eat a banana either. A day of low sodium salt gives you about as much potassium as a banana. So, I don’t mean to minimise the potential risk for people with undiagnosed kidney failure.”

“Salt is a serious problem. We don’t think of it like pesticide or salmonella contamination, but it actually kills a lot more of your customers.”

Chemical confusion

One argument for not replacing sodium with other ingredients has been that consumers would likely not want to see nor understand the chemicals used to replace it with on the back of their packets. But, Frieden agrees, such a point is largely a red herring. He says not many people use the information on packaging, nor do they understand it in any case. But packaging could help play a big role on other ways.

700,000

The number of deaths related to heart disease in those aged 70 and older that could be prevented if the salt reduction target was met.

Resolve to Save Lives

One development he believes is having a huge impact is the black stop sign, first used in Chile. Since its introduction in 2016, the mark has alerted Chilean consumers to excessive ingredients including salt, sugar and saturated fats, with the words ‘alto en’ or high in placed on octagonal black labels on packaging. The concept has since spread to Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Israel.

Frieden welcomes the impact they’ve had, suggesting they have helped change both options and the choices made by manufacturers and the public alike.

“What we found is that very quickly companies reformulated to meet the standard and very quickly consumers changed what they bought,” he says. “So, after decades of pleading with companies to change and hectoring people to choose healthier foods, actually Chile initially – and then other countries – have come up with a way to do it.” Albeit it’s not a solution that is popular with industry, he suggests: “Anything that says ‘eat less’ is not good for the bottom line… but it’s clear that the black stop sign that says ‘too high in sodium’ has resulted in something like a third of products being reformulated within months.”

Chile’s decision was predominantly taken to drive down levels of obesity. In the middle of the past decade the country’s Ministry of Health warned that two-thirds (67%) of those aged 15 and over were obese. At the same time the country’s leading causes of death were cardiac ailments and cancers, specifically stomach and gallbladder – arguably lifestyle related – which accounted for half of all recorded deaths.

Latin America leading

The success of the policy and its replication among Chile’s Latin American neighbours proved government action could help elicit change. But, warns Frieden, there has to be that level playing field he previously spoke of. “If there is a society wide policy, it’s going to be easier for you [manufacturers] to make the changes,” he says. It’s a view he supports by saying if one company acts in isolation, there’s a risk of that having a negative impact – perhaps hitting its market share, for example. But if all change together, such issues are diminished. It’s a level playing field, achieved through by regulation, that “gets you there” he says.

“The industry may not like it but stop signs and warning labels are the best practice,” he adds. “With all due respect for industry, we usually hear ‘it’s impossible, we can’t make that change’. Then when the change becomes inevitable, it’s a lot easier than even the industry thought.” As parts of Latin America have shown in current time, warning labels can help cut sodium consumption dramatically and manufacturers in that region are now actively taking steps to avoid having those labels on their packaging, reducing sodium usage voluntarily.

Whatever the answer, there is a clear and growing need to find it. “Salt is a serious problem,” concludes Frieden. “We don’t think of it like pesticide or salmonella contamination, but it actually kills a lot more of your customers… If we just step back for a minute, by the best available estimates excess sodium consumption is the single deadliest problem with our food.”