It has long been accepted that legumes (such as soybeans, beans and peas) are generally ‘good for you’, while meat is considered ‘less good’. However, consumers are creatures of habit, and switching from red meat to meat substitutes remains a notoriously difficult marketing challenge.

Most plant-based meat and dairy alternatives have lower levels of saturated fat and higher fibre than their animal-derived counterparts. They often also boast substantially lower environmental impacts – such as reduced greenhouse gas emissions and more efficient water and land use. Yet, while these alternatives may be useful pathways to a healthy, sustainable diet, their nutritional value can vary significantly based on processing techniques, environmental impact and even the brand. For instance, some plant-based alternatives fall into the undesirable category of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Even so, many of these products still meet dietary recommendations because they provide adequate fibre and keep saturated fat levels low.

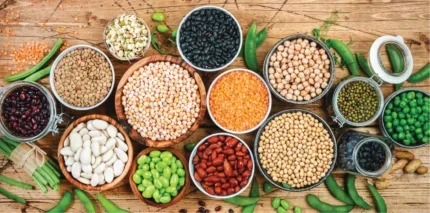

A recent Oxford University study led by Dr Marco Springmann of the Environmental Change Institute, published in December 2024 and titled ‘A multicriteria analysis of meat and milk alternatives from nutritional, health, environmental and cost perspectives’, lays out the findings clearly. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the study found that beans and peas rank best as meat and milk replacements when evaluated on nutritional, health, environmental and cost metrics. In fact, they outperformed processed products such as veggie burgers, plant milks and even lab-grown meat – which ranked worst.

The study went on to state that choosing legumes over meat and milk could reduce nutritional imbalances in high-income countries (including the UK, US and Europe) by about 50%, while also cutting greenhouse gas emissions by more than half. Moreover, it indicated that such a switch could reduce mortality rates from diet-related diseases by roughly 10%.

Researchers assessed a wide spectrum of alternatives: traditional products such as tofu and tempeh, processed options like veggie burgers and plant milks, prospective products including lab-grown beef, as well as unprocessed foods like soybeans and peas. While it is important to distinguish between processed and unprocessed legumes, the study found that even processed plant-based foods (e.g., veggie burgers and plant milks) still offer substantial benefits over meat – albeit with emissions reductions and health improvements roughly 20–30% lower than those provided by unprocessed legumes. Consumer costs for these processed alternatives were estimated to be about 10% higher than those of current diets.

Notably, unprocessed legumes emerged as the clear winners in terms of nutrition, health, environmental impact and cost. A surprising entrant was tempeh.

Tempeh: a surprising star

Tempeh is a traditional Indonesian food made from fermented soybeans using a natural culturing and controlled fermentation process that binds the soybeans into a firm cake. A fungus – either Rhizopus oligosporus or Rhizopus oryzae (commonly known as tempeh starter) – is used during fermentation. This process allows tempeh to retain much of the nutritional properties of soybeans without extensive processing or additives, giving it an edge over more processed alternatives such as veggie burgers.

The study also presented other surprises. For example, the data suggested that lab-grown meat is not yet a competitive product compared even with conventional meat. At current technology levels, its emissions can be as high as those of beef burgers and its production costs can be up to an eye-watering 40,000 times higher. Although future investments and technological advances might lower these figures, significant financial commitment would be required. For Springmann, given that affordable and effective alternatives to meat and milk already exist, the prospect of public investment in lab-grown meat and ultraprocessed burger patties is a tough sell.

“Our previous research strongly suggests that adopting predominantly plant-based dietary patterns – from vegan and vegetarian diets to flexitarian diets with low to moderate amounts of animal products – can substantially reduce environmental footprints and lower the risks of developing diet-related diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer and diabetes compared with the average Western diet,” he explains.

“Instead of completely overhauling one’s diet, many people find it easier to start by reducing the most impactful sources of meat and dairy. That is why we focused specifically on meat and milk alternatives in our study. We found that minimally processed legumes such as beans and peas consistently outperformed most other alternatives on metrics including nutrition, dietary health, environmental impact and cost.”

More processed alternatives, such as veggie burgers and plant milks, performed less well – except in terms of cost, where they were about 10% more expensive – yet they still performed better than the meat and milk they are designed to replace. In contrast, lab-grown meat fared poorly across all dimensions, matching conventional meat in its lack of nutritional and health benefits while remaining prohibitively expensive even when factoring in the potential for future technological improvements.

Changing consumer habits and market trends

Old habits die hard, and consumer dietary resistance remains a significant barrier. Trends in high-income countries like the UK, US and across Europe show that meat and milk consumption is largely steady, with only tentative signs of decline – insufficient, however, to reduce the environmental impact of our diets to safe levels. Still, meat and milk alternatives are growing in popularity, even though recent increases in the cost of living have led to temporary dips in their uptake.

“Our analysis suggests that the costs of many meat and milk alternatives are a major factor limiting their popularity,” says Dr Springmann. “Choosing basic ingredients such as beans and peas is not only cheaper but also better for health and the environment.”

One promising area of research is the growing movement towards plant-based meat, driven by concerns for health, the environment and animal welfare. A study from Kansas State University, published in the Journal of Food Science in December 2022, found that pea protein isolate and concentrate have become popular ingredients in texturised plant protein. Understanding the role of starch and fibre in structuring textured pea protein could lead to innovations that reduce costs and increase the sustainability and nutritional quality of meat alternatives while achieving desired textural attributes.

While ongoing research and development are critical, political considerations and regulatory landscapes also play significant roles. For example, the EU’s ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy seeks to reduce dependency on crops like soy that are grown on deforested land – a measure further supported by the EU Deforestation Regulation, due to come into effect on 30 December 2025.

According to Gijs Kleter, food safety scientist at Wageningen University & Research, “Soy and cacao, among other commodities, are considered ‘risky’ (alongside coffee, palm oil, timber and livestock). They must be certified as deforestation-free, meaning that products should be traceable to individual farms using geospatial coordinates.” Kleter emphasises that traceability is key. “My colleagues at WFSR, for instance, can determine the geographical provenance of palm oil based on specific compositional features. Major efforts are under way to improve this process.” He also notes that soybeans remain competitively priced and offer several functional benefits that are hard to match with other alternatives, making their substitution challenging.

Emerging alternatives and changing consumer attitudes

Meanwhile, other plant-based alternatives are gaining favour. Popular options include pea protein, wheat gluten and mycoprotein, with recent additions such as proteins from oilseeds (e.g., canola meal and sunflower meal) and a resurgence of fava beans. However, concerns persist: Kleter highlights worries that increasing consumption of soybean-based products (such as soy drinks, tofu and tempeh) might lead to hormonal effects in pregnant women, children and adolescents. So much so that the UK, Norway and the Netherlands have issued consumer advice notices recommending moderation for these at-risk groups.

Other hazards include pesticide residues and natural toxins (mycotoxins) that can form when mould grows on crops in the field or on harvested produce. “Regulated products such as pesticides should always be safe when used according to good practices,” Kleter explains. “During pre-market risk assessments, assumptions are made based on current consumption data; if consumption changes significantly, these estimates must be revised.”

Looking ahead, a recent pan-European survey conducted by ProVeg – in partnership with the University of Copenhagen and Ghent University – offers useful insights into consumer trends. The data suggest that 57% of respondents incorporate legumes into their diets at least once a week, while 28% regularly consume plant-based alternatives and 17% regularly consume legume-based products. Crucially, 43% of consumers plan to increase their consumption, provided that the products remain tasty (53%), healthy (46%) and affordable (45%). Supermarkets have already begun responding by adding more grain and pulse products to their private-label assortments. Examples include Tesco’s quinoa and red split lentils and Dutch chains like Albert Heijn (with its gluten-free lentil pasta) and Jumbo’s three-colour organic quinoa mix. While the growth of private-label products is a promising sign, widespread adoption of plant-based alternatives may still be a gradual process.